There was nothing preordained or inevitable about this outcome.

Shah Alam is also there in 1765, in the wake of the Battle of Buxar, dismissing his revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa and replacing them with Company men in an act of what Dalrymple describes as “involuntarily privatization.” “Before long,” he writes, thanks to Indian loot, “the EIC was straddling the globe.” “He’s there at the age of 16 when Nader Shah rides into Delhi, when Delhi’s still at its peak, and he’s there as this broken, blind old man in his nineties at the end, when General Lake rides in. “It took forever to work out that the main character was actually Shah Alam,” he says. “The difficulty was working out what the narrative would be.”įor all the colorful, conniving Company men who came to the sub-continent in the period Dalrymple covers-namely, the years of Mughal decline, when “the once peaceful realm of India,” as one scholar put it, “became the abode of Anarchy”-it was ultimately an Indian who provided him with the through-line he needed.

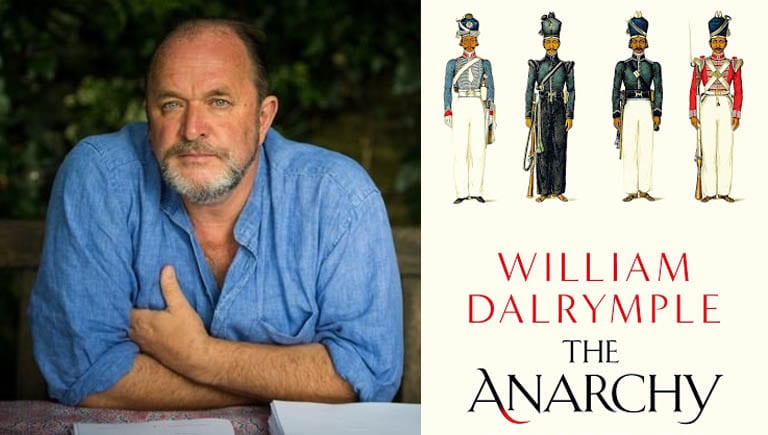

“What I hadn’t ever written before was kind of a big, sweeping macro-history, and I didn’t know how to do it at all,” he says. The aforementioned corporate violence seems troublingly familiar, too-think Halliburton, Blackwater, the application of the shock doctrine-though the book allows readers to make most of the connections themselves. The big crashes of 10 years ago make it much more interesting to a historian today.” “What is interesting, though,” Dalrymple says, “is that, if you read Victorian histories of the Company, this bailout barely warrants a footnote.

The Company’s responsible for half of all British trade by then. It’s the largest loan ever given to a British company up to that point. “The most obviously relevant moment is when the company goes bust in 1772 and has to borrow massive sums of money. Sometimes it looks as though the Company is winning-bribing the state to alter the law, guarantee its monopolies, provide it with military assistance-and at other times it seems as though the state is winning, which it ultimately does in 1858, when the Company is nationalized.” “Behind the story of the Company’s conquest of India is this tussle between the two. “The story of the East India Company is the story of this odd dance between the power of the corporation and the power of the state,” Dalrymple says. He points to some of the more obvious ways in which this is the case: the East India Company’s invention of corporate lobbying and its role in the world’s first-ever lobbying scandal, its dubious status as the recipient of one of history’s first government bail-outs.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)